Join 1.3 Crore+ Indians

who trust us for

who trust us for

Trading & Investing

4.5+

Avg. app rating- Backed by the Best

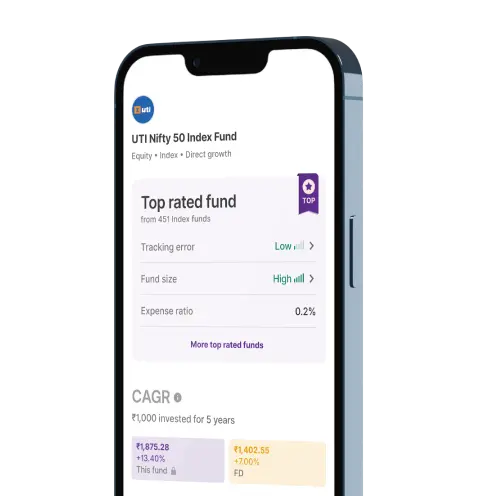

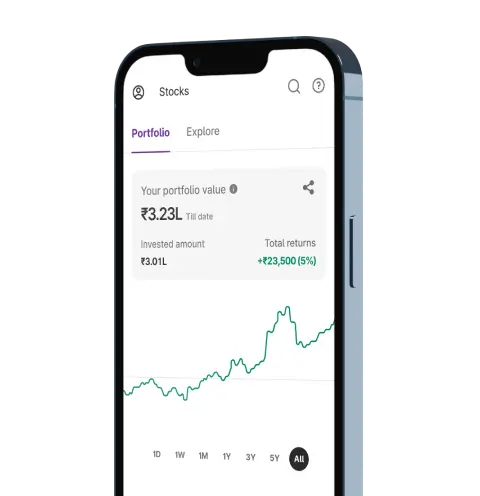

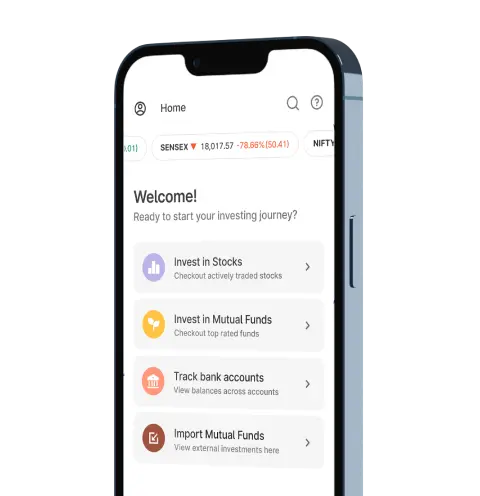

Upstox for Investors

Invest Right, Invest Now in Stocks, Mutual Funds, and IPOs

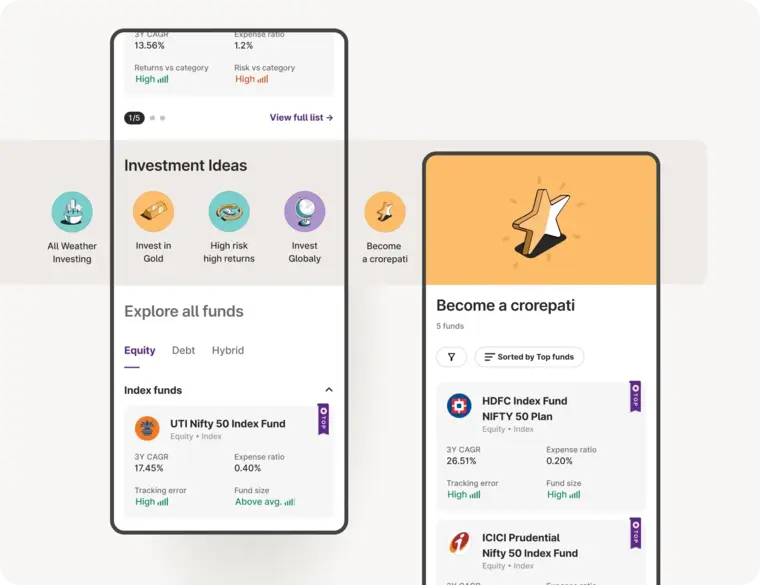

Investment Ideas

News & Insights

Order Placement

Top rated Funds | Best for Beginners | Top 30 actively traded Stocks

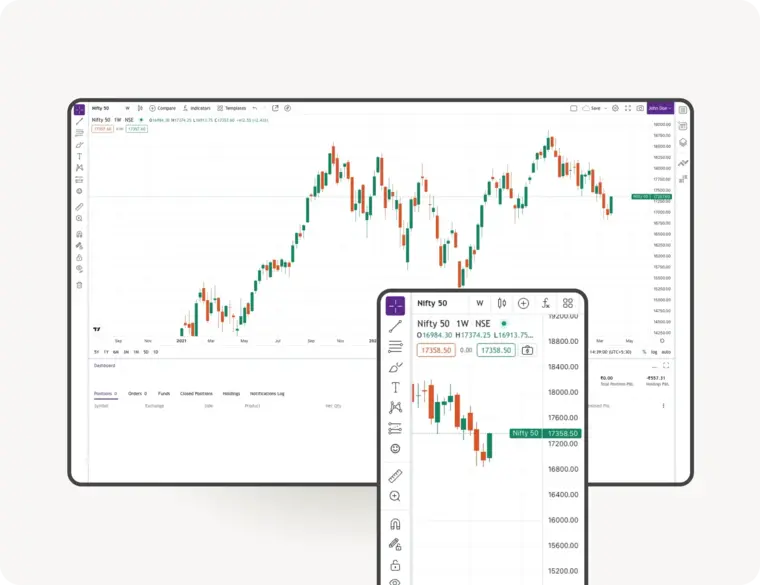

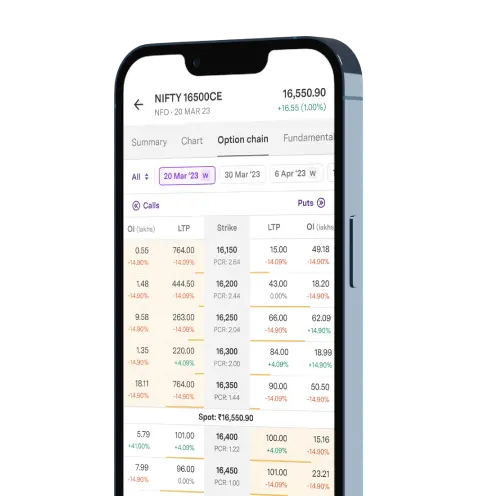

Upstox Pro for Traders

Powerful trading in Equities, Futures, Options, Commodities and Currencies made simple

Powerful Charting

Powerful Discovery

Powerful Execution

TradingView | 8 charts at once | 100+ indicators | 80+ Drawing tools