Upstox Originals

Is borrowing finally weighing on state governments?

5 min read | Updated on November 21, 2025, 19:52 IST

SUMMARY

Just like the central government, states actively borrow for growth and investment. But what happens when borrowing overshoots and borrowing costs start to become sticky? Even as state government borrowing dropped by over 50% in October 2025, interest rates remain stubbornly high. So, what is spooking investors away from state bonds?

State borrowing dropped sharply, from ₹1.21 trillion in September to just ₹57,010 crore in October 2025.

For most of FY26, states had no trouble borrowing from the bond market. They raised money for roads, metros, irrigation and welfare programmes; and investors were comfortably buying those bonds.

But things changed over the past couple of months.

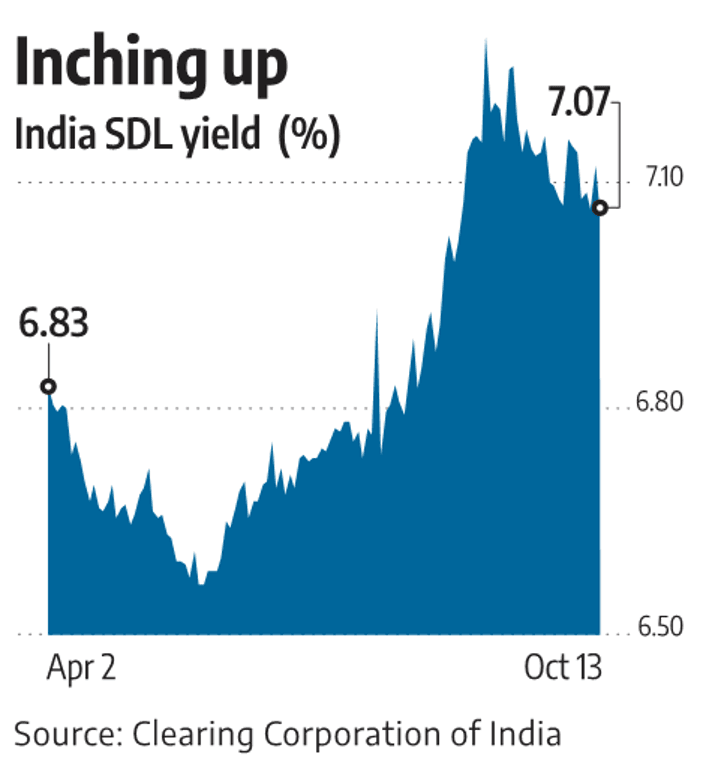

State borrowing through State Development Loans (SDLs) dropped sharply, from ₹1.21 trillion in September to just ₹57,010 crore in October. Even last October’s ₹64,842 crore was higher. One potential reason for the same could be rising state borrowing costs. The average 10Y SDL yield moved from around 6.85% in April to 7.09–7.17% by August, and remains above 7% for many states even in November.

Before we dive in deeper, let’s just clarify - what are SDLs? Just like the central government, states go to market and raise money via State Development Loans (SDLs). Simply put, these are bonds issued by the state government to raise capital.

The question is - why does it matter? So what if states borrowed less money for one month? Its not just that states borrowed lesser for one month that is surprising, its that yields did not come down. If state borrowing reduces, that theoretically the interest rates should have come down. But that did not happen.

Despite a small reduction in the cost of borrowing (yields), it remains stubbornly over 7%. The spread between state and central government borrowings has also not reacted as expected.

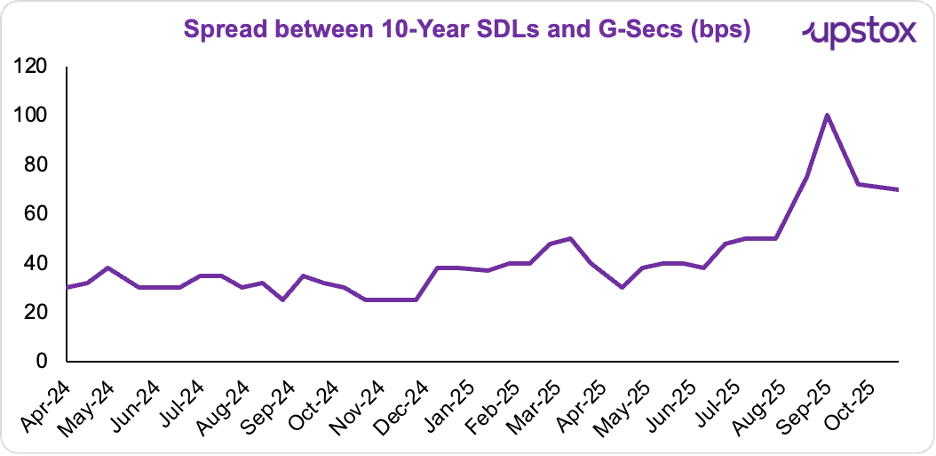

Spread here means the difference between the borrowing costs of the state and central government. Since the central government is larger, it borrows more often, and its bonds are liquid, they are able to borrow at better rates than the states.

As can be seen from the chart below, the usual gap (spread) between state and central government borrowing is in the 30–40 bps range.

In April 2025, the spread between the 10-year benchmark SDL and the 10-year benchmark G-Sec was only about 32 bps, right in the normal band. By July 2025, it had risen to around 43 bps, indicating the first signs of stress. But in late September, it jumped to about 106 bps, the highest since April 2020. Even through October, it stayed elevated at 70–75 bps.

Source: ICRA

Why are SDL yields rising?

States borrowed too much, too quickly

The bond market has significantly priced the fact that states have borrowed far more than their stated budgets. For instance, issuance in SDL auctions on August 26 reached ₹28,892 crore compared to a targeted ₹21,400 crore, and on September 2, it reached ₹29,082 crore compared to a projected ₹20,850 crore. In order to absorb the excess issuance, investors demand higher returns due to supply saturation caused by this magnitude of overshooting.

States like West Bengal, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh have significantly increased their borrowing programs, which has increased the pressure on yields. The market expects rising pressure on SDL yields to continue as borrowing picks up speed in December and January, when analysts predict a pile-up. Investors have better options right now

Long-term institutional investors, such as insurers, pension funds, and provident funds, have reduced their SDL purchases, transferring some to equities amid strong market performance.

According to the revised PFRDA guidelines effective October 1, 2025, non-government NPS subscribers can now allocate up to 100% of their contributions to equity schemes; up from the earlier 75% cap. This shift has encouraged greater movement toward equities, reducing demand for SDLs and other debt instruments.

Why are rising SDL yields a concern?

Weakening investor returns

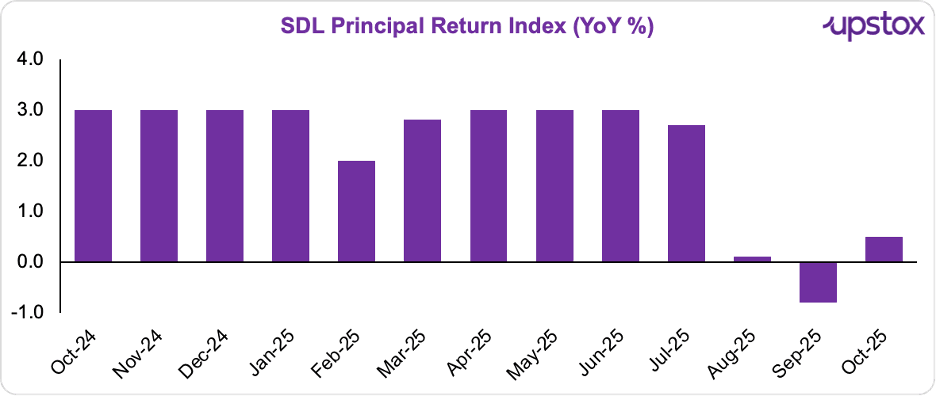

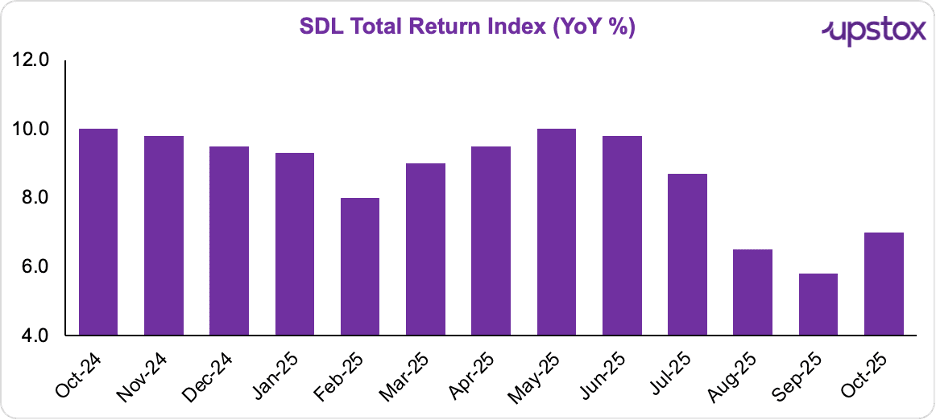

Rising yields are reducing investor returns, as evidenced by the declining Principal Return Index (PRI) and the softening Total Return Index (TRI).

Source: CCIL

Source: CCIL

Capital investment will be overcrowded

14–21% of state revenue is already allocated to debt payment. States will have less money to spend on infrastructure, health, education, irrigation, and rural development due to higher borrowing costs. Medium-term growth expectations may be hampered by this, particularly in states where public investment is a major source of economic momentum.

Debt servicing costs

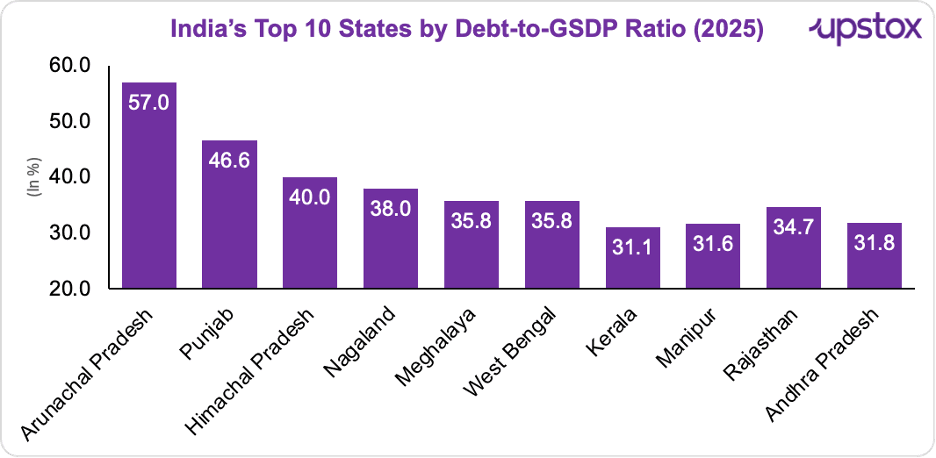

Many states continue to have high debt-to-GSDP ratios, which limits their budgetary headroom and raises perceived credit risk. This ranking is dominated by states like Himachal Pradesh (40%), Punjab (46.6%), and Arunachal Pradesh (57%).

Source: Livemint

And, an increase in yields of 40 basis points results in a much greater interest burden. A state borrowing ₹20,000 crore would pay an additional ₹80 crore in interest each year and ₹800 crore over the course of a normal 10-year maturity. The financial space available for crucial development initiatives is directly diminished by such cost increases.

What’s next?

The RBI will probably continue to be strict about limiting state borrowing in the future. It has already recommended states to spread out their issuances rather than packing everything into pricey, long-dated bonds after identifying growing SDL costs as a danger. This change indicates that the RBI may no longer cushion auction tails as it formerly did.

And reforming credit ratings for SDLs is slowly making its way into policy discussions. As Economic Affairs Secretary Ajay Seth put it, “Even starting the process of rating state government loans will be an important signal… Today, state debt papers are treated more or less the same, irrespective of whether the state debt-to-GDP ratio is 50% or 20%.”

If that transition occurs, SDLs may soon begin pricing fiscal discipline in considerably more transparent ways; and the gap between strong and weak governments may increase much faster than previously.

By signing up you agree to Upstox’s Terms & Conditions

About The Author

Next Story