Upstox Originals

India’s trade tensions keep mounting, is CBAM the next flashpoint?

8 min read | Updated on January 13, 2026, 18:44 IST

SUMMARY

What happens when climate policy starts acting like a trade barrier? That’s what Indian exporters face as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) puts a carbon price on imports like steel and aluminium. With a wide carbon price gap and limited compliance capacity among MSMEs, nearly 10% of India’s EU exports are exposed.

According to the GTRI, India’s steel and aluminium exports to the EU fell 24.4% in FY2024–25

From January 1, selling to Europe just got more expensive for Indian exporters.

Not because demand is falling.

But because Europe is putting a tariff-like price on carbon.

Not directly, of course. But if you export steel, aluminium, cement, or other carbon-heavy goods to the EU, the bill is coming.

It’s called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Part of Europe’s bigger “Fit for 55” plan, to cut emissions by 55% by 2030.

And this isn’t a small problem. Because Europe matters.. a lot.

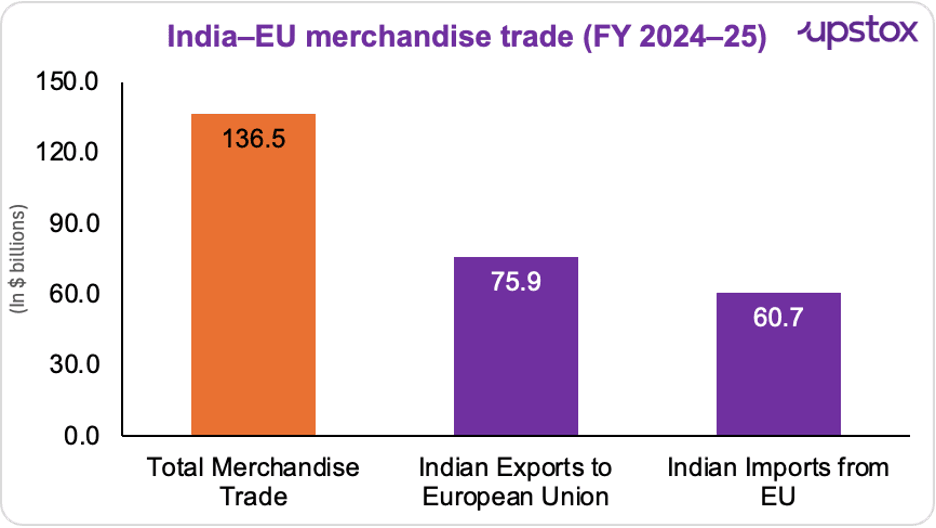

In FY2024–25, India–EU merchandise trade touched $136.53 billion. Indian exports alone were worth $75.85 billion, more than half the trade.

Source: BS

Now here’s the part worth paying attention to.

The impact is already showing up in the numbers.

According to the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI), India’s steel and aluminium exports to the EU fell 24.4% in FY2024–25, from $7.71 billion to $5.82 billion.

Steel took the biggest hit. Exports plunged 35.1% to $3.05 billion. Aluminium shipments slipped nearly 10%.

And here’s the surprising bit.

From October 1, 2023, the EU simply made carbon-emissions reporting mandatory under CBAM. No payments. No penalties. Just paperwork.

But even that was enough to slow shipments.

Which tells you something. If reporting alone can dent exports, actual carbon pricing could hurt even more.

And yes, we’re sure you’d like to see what’s coming next.

Source: TOI

What actually is CBAM?

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is the EU’s way of saying: “If our companies pay for carbon, your exports should too.”

It puts a carbon price on carbon-intensive imports such as iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen. Over the next few years, the EU plans to extend CBAM to cover all major industrial products.

How does it work?

Start with the problem Europe is trying to fix. European companies already pay for their emissions through the EU’s carbon market.

But foreign producers don’t.

Which means cheaper, high-carbon imports can undercut cleaner production inside Europe.

CBAM is meant to close that gap.

It applies Europe’s carbon rules at the border, so exporters don’t gain an advantage just because climate rules back home are looser.

Now to the maths. (It’s simpler than it sounds.)

The CBAM bill depends on two things: – How much carbon was emitted while making the product – The EU’s carbon price, currently around €80 per tonne of CO₂

Multiply the two, and you get the CBAM charge.

If a country already prices carbon domestically, that amount is deducted. If it doesn’t, exporters pay the full cost.

India falls into the second bucket.

There’s no nationwide carbon price yet, which means Indian exporters currently face the entire CBAM burden.

And while European buyers pay the charge on paper, the cost rarely stays there. It usually flows back to exporters, through lower prices, tougher negotiations, or buyers switching suppliers.

Which is why cleaner producers have an edge.

Lower emissions mean a smaller CBAM bill, and fewer reasons for buyers to walk away.

What is its impact on India?

India’s steel has a carbon problem

India’s steel industry is among the most carbon-intensive in the world.

According to a European Commission study, producing 1 tonne of finished steel in India emits about 2.6 tonnes of CO₂, 20–25% higher than China and well above the global average of 1.92 tonnes.

The reason is structural.

India relies heavily on coal-based processes like direct reduced iron (DRI) and blast furnaces, which emit 3.0–3.1 tCO₂ per tonne.

Compare that with scrap-based electric arc furnaces, which emit just 0.7 tCO₂ per tonne. The outcome is predictable.

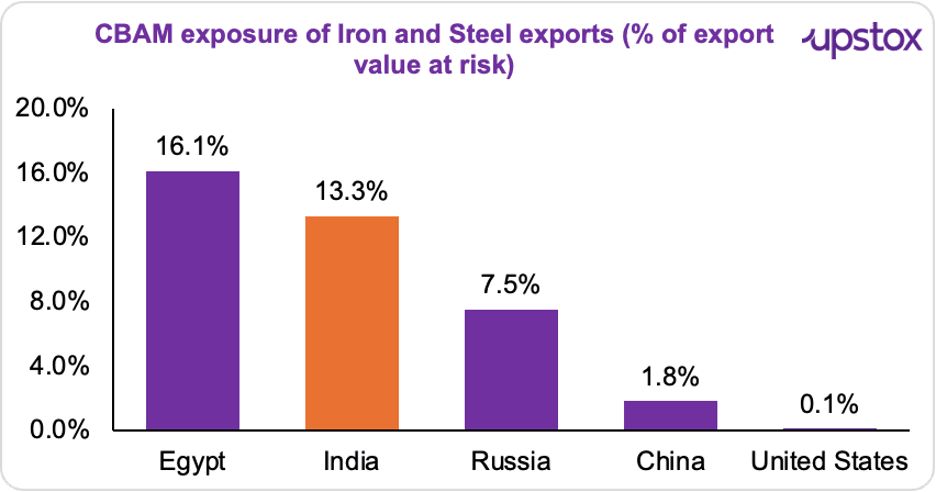

The World Bank’s CBAM Trade Exposure Index flags India as one of the most exposed steel exporters, with over 13% of export value at risk due to excess carbon costs, far higher than China or the US.

Source: World Bank

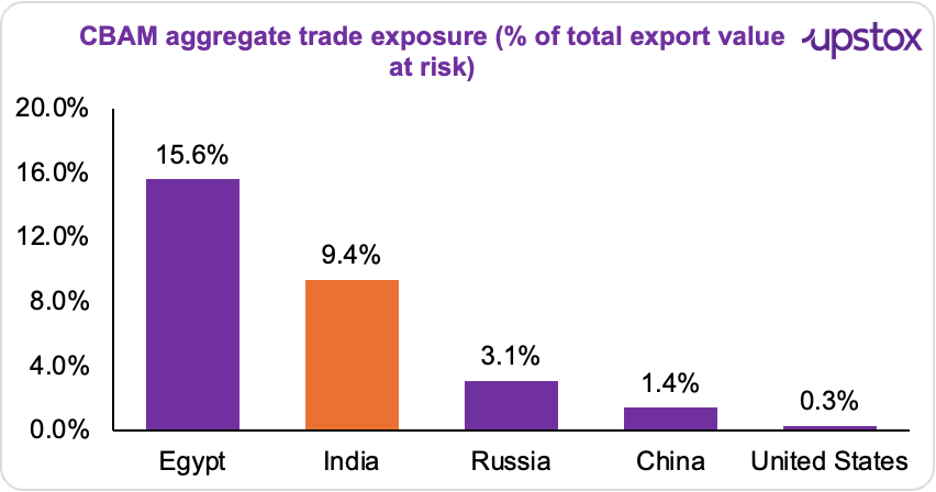

Aggregate trade exposure isn’t small either

If you zoom out from individual sectors and look at the bigger picture, the risk doesn’t disappear.

The World Bank’s CBAM Aggregate Trade Exposure Index combines two things: how carbon-intensive a country’s production is and how dependent it is on EU markets across all CBAM-covered sectors; steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers and more.

For India, that number stands at 0.0935. About 9.35% of the value of India’s exports to the EU is exposed to competitiveness loss under CBAM, compared with EU producers.

Source: World Bank

Then there’s the MSME problem

And this is where things get even trickier.

Smaller exporters in India could be hit the hardest.

Many MSMEs don’t have access to plant-level emissions data for the steel or aluminium they use. They source from large producers who often don’t share verified carbon numbers.

When that data is missing, EU authorities don’t wait.

They apply default emission values, conservative estimates set near the highest benchmarks.

According to GTRI, these defaults can be 30–80% higher than actual emissions, instantly inflating carbon costs.

And the pressure only rises from 2026, when independent emissions verification becomes mandatory.

Only EU-recognised or ISO 14065-compliant verifiers will be accepted. For many MSMEs, that could be one compliance step too far.

Macroeconomic impact with industry-level implications Under a pure CBAM scenario, India’s GDP is estimated to decline by 0.02–0.05%, according to the Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP).

But this small headline number hides a sharper sectoral impact. CBAM-exposed exports account for only about 0.2% of India’s GDP, yet iron and steel make up nearly 90% of affected shipments. So while India’s overall growth may barely register the hit, carbon-intensive industries, especially those dependent on EU markets, face a disproportionately higher competitiveness shock.

What has India done about it so far?

India has pushed back on CBAM since 2023, calling it “unfair” to developing countries at the WTO and with BRICS partners, while also opening bilateral talks with the EU.

It launched the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS) to begin building a domestic carbon market for energy-intensive sectors from 2026. In 2024, Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said India was preparing to take up CBAM “very strongly within the rules of the WTO”, even as EU–India technical talks focused on emissions reporting and aligning CCTS during CBAM’s transition phase.

At the firm level, companies like JSW Steel and Hindalco invested in efficiency and green hydrogen.

Now, what can India do?

According to GTRI, there’s no quick fix. But a few options are clear.

First, pricing carbon at home. The idea is straightforward. If India charges for carbon domestically, exporters can subtract that cost when paying CBAM in Europe. But there’s a catch. Europe’s carbon price is around €80 per tonne. Matching that overnight would be unrealistic for Indian industry.

That’s why, as Ajay Srivastava of GTRI explains, India needs a “gradual, calibrated carbon pricing mechanism”, one that gives MSMEs time to adjust, without making exports uncompetitive.

Second, diplomacy. The EU has reportedly given the US some breathing room recently, through longer phase-in periods or partial waivers. The view is that India should push for similar flexibility in its negotiations with Brussels.

Because without it, CBAM could turn into a permanent trade barrier, instead of a temporary transition measure.

And finally, exporters themselves need to prepare. That means building internal systems to understand CBAM costs, starting with a “shadow carbon price”, or a notional EU-style carbon cost, to see how margins might change under European benchmarks.

It also means preparing standardised CBAM data packs for each plant. These would include production routes, emissions per tonne, verification statements, and audit contacts.

According to GTRI, “such data packs may soon become as essential as invoices or certificates of origin.”

Before you scroll away

CBAM makes one thing clear, carbon is no longer just an environmental issue, it’s a pricing variable, a contract clause, and a competitiveness filter rolled into one. For Indian exporters, the challenge isn’t just paying more; it’s learning to measure, price and negotiate carbon as part of everyday business.

Those who adapt early could still hold their ground in Europe. Those who don’t may find that access to markets now depends as much on emissions data as it does on quality or cost.

About The Author

Next Story