Upstox Originals

India's rare earth reckoning: Navigating Chinese ban

7 min read | Updated on August 13, 2025, 18:54 IST

SUMMARY

It's been over three months since China curbed the export of critical rare earth minerals, putting India’s EVs, smartphones, and defence production at risk. With Beijing controlling the majority supply and, more importantly, refining, are we really at their mercy? Does India have alternative paths to protect itself? This article explores where India can turn for alternatives and how it’s building self-reliance.

China controls a majority of the world's rare earth supply

Last month, India registered 1,88,804 electric vehicles. In the June quarter, smartphone shipments rose 8% YoY, hitting their highest-ever Q2 by value. But what if next month, factories fall silent, not because demand has slowed, but because we’ve run out of the rare earths that power them?

While this may sound like an exaggeration, when one supplier controls most of the mining and processing, a policy tweak there can stall production here.

Why this matters: rare earth elements (REEs) are the quiet parts inside our growth story. They power magnets, motors, batteries, chips and so much more. If the flow stops, assembly lines slow, costs rise, and targets slip. That’s why India needs a Plan B (and maybe even C) for REEs.

India’s current rare earth scenario

Rare earth minerals (REMs) and rare earth elements (REEs) are like the “vitamins” of modern technology, needed in small amounts but essential for things to work. REMs are raw mineral ores, while REEs are the valuable metals inside them, like neodymium, lanthanum, cerium, and dysprosium. Rare earths are a group of 17 elements found in the Earth's crust.

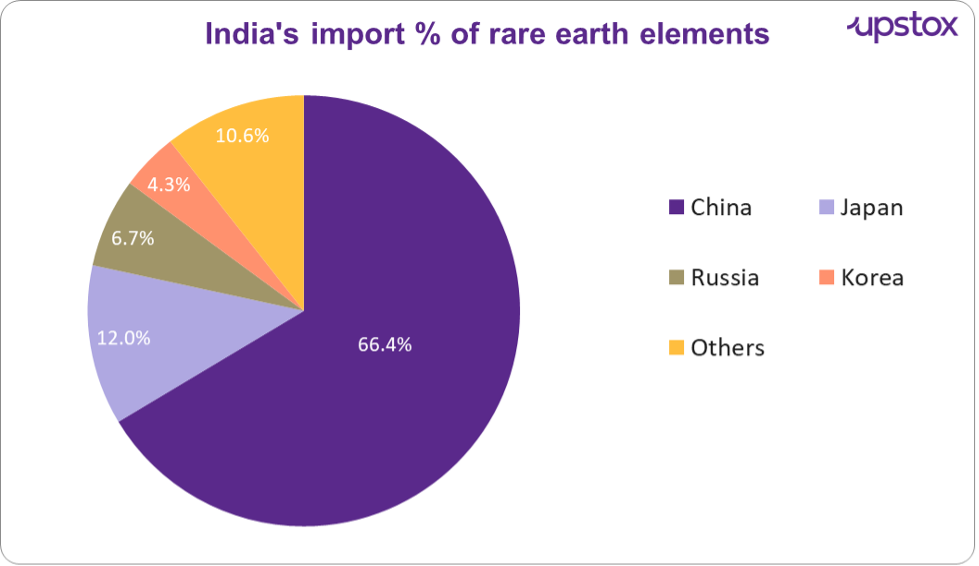

India imports over 70% of its REMs and as seen below, the majority of it is from China.

Source: Reply to part (a) of Lok Sabha unstarred question No. 5253 answered on 02.04.2025

These metals power everything from EV motors and wind turbines to phone speakers and defence equipment, and other high-tech gear. Without them, production slows, costs rise, and projects stall. When one country controls most of your supply and hints at export restrictions, the risk is clear. That’s exactly where India stands today.

This dependence is risky enough, but it also raises a key question: are these resources genuinely scarce, or is our problem something else? but first why are we in this position?

Why did China stop exporting REM’s ?

China's action to limit exports of rare earths has been seen widely as a move against the United States in the face of trade tensions. As such, the export ban is not specific to India but more global in nature.

Are rare earths really rare, or does China just mine the most?

The term "rare earth" is a bit misleading; these metals are not as rare as their name would suggest. The real challenge is processing and extracting them. It is a costly, complicated process that involves sophisticated technology and a gentle touch because it can produce toxic and even radioactive waste.

As per reports by CSIS globally, it takes on average 18 years to develop a mine which costs $500 million and $1 billion to build a mine and separation plant.

China's strength lies in investing early in the whole supply chain, that is, mining, refining, and making end products such as magnets. This allows it to supply the world in bulk at lower costs and become the first choice for most countries.

India has indigenous reserves, particularly monazite sands in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Odisha. However, limited processing capacity and high production costs keep us dependent on imports.

Alternative sources beyond China

If China is the giant in the rare earth world, it’s not the only game in town. Several countries are emerging as viable partners for India, each bringing its own strengths to the table.

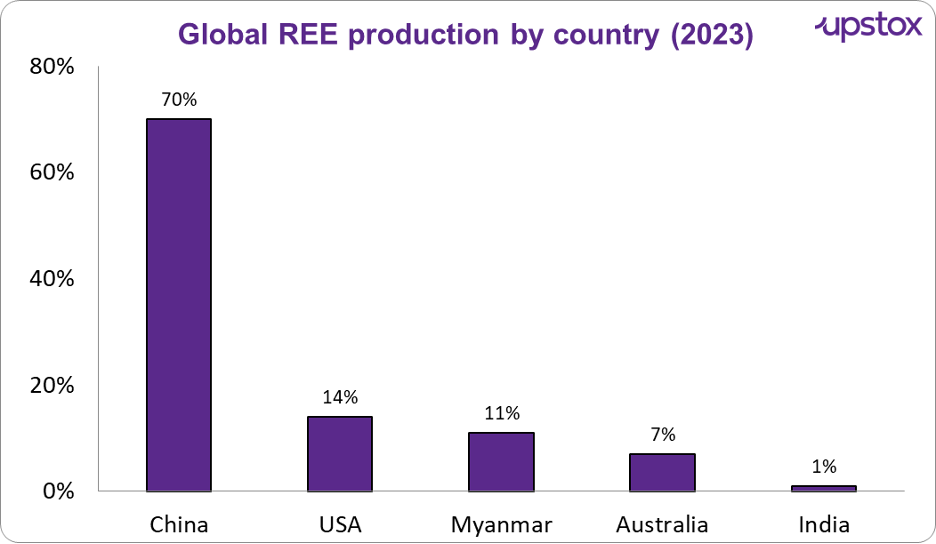

Source: Statista

Finding alternatives to China’s rare earth supply isn’t as simple as picking new partners off a map. Many potential sources are in regions where India’s relationships are still evolving, from Latin America to parts of Southeast Asia. The goal then, isn’t instant alignment, but building strategic ties where interests overlap.

Australia remains a friendly and reliable option, but in other geographies, India will need to balance diplomacy with supply chain needs, working through multilateral platforms and investment partnerships to create stable access.

Reducing dependence: from substitutes to self-reliance

India’s push for rare earth independence

India is working on multiple fronts to cut its dependence on Chinese rare earths. A big part of that plan is tapping into its own reserves, the third largest in the world, estimated at 12.7 million tonnes. These are spread across several states and include carbonatites, beach sand placers, and other rich deposits.

State-wise mapping of REE deposits in India

| State | Deposit type | No. of deposits | Resources (million tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | Carbonatites, beach sand placer deposits | 24 | 3.78 |

| Gujarat | Carbonatites | 2 | 0.07 |

| Jharkhand | Yttrium-rich xenotime placers, residual concentration from weathering rocks | 1 | 0.21 |

| Kerala | Beach sand placer deposits | 35 | 1.84 |

| Maharashtra | Carbonatites | 5 | 0.004 |

| Odisha | Beach sand placer deposits | 12 | 3.16 |

| Tamil Nadu | Carbonatites, beach sand placer deposits and alkaline rocks | 50 | 2.47 |

| West Bengal | Carbonatites | 1 | 1.2 |

| Total | 130 | 12.73 |

Source: orfonline.org

This domestic focus is backed by policy moves such as the National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM) and amendments to the Mines and Minerals Act, which now allow private players into exploration and magnet manufacturing.

At the same time, India is securing supply from friendly nations like Australia and exploring deals in Latin America, Oman, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka. Recycling, research into substitutes, and new magnet technologies are also part of the mix.

Shift to LREs

Some manufacturers aren’t waiting for policy alone to deliver results. Bajaj Auto, for example, has turned to low rare earth (LRE) magnets to keep its EV production running despite supply risks.

Switching to LRE magnets required re-engineering motors to maintain performance, but it turned a feared “zero production” month into output levels of around 50% for the Chetak scooter and 70% for the Go electric three-wheeler. With supply stabilising, the company expects to recover fully by October, this is proof that industry innovation can bridge gaps while longer-term self-reliance plans take shape.

Can LRE’s be used across the board? That remains to be seen. And the transition is not easy.

Beyond mining – India’s wider strategy

India’s rare earth strategy stretches well beyond mining. Internationally, Australia is becoming a key partner, while Argentina, Brazil, and Oman are on the radar for future deals. At home, state-run IREL and private players like Sona Comstar and Vedanta are scaling up magnet manufacturing.

The National Critical Mineral Mission is pushing innovation in processing, recycling, and designing magnets that need less or no rare earths at all.

Challenges and the road ahead

India’s rare earth ambitions face steep hurdles. Exploration remains limited, with only a fraction of reserves mapped in detail. Processing capacity is scarce, and refining rare earths is both capital and technology-intensive. Environmental clearances often slow projects, while high production costs make local output less competitive than imports from established players like China.

But these challenges also frame the opportunity. Demand for rare earths is set to surge as electric vehicles, renewable energy, and high-tech manufacturing expand. The geopolitical need to diversify supply chains is urgent. Closing the gap will require scaling up exploration, investing in modern refining technologies, and building globally competitive supply chains the steps that could determine whether India stays import-reliant or emerges as a serious player in the global rare earth market.

By signing up you agree to Upstox’s Terms & Conditions

About The Author

Next Story