Upstox Originals

The next white revolution wont need cows?

9 min read | Updated on December 22, 2025, 16:32 IST

SUMMARY

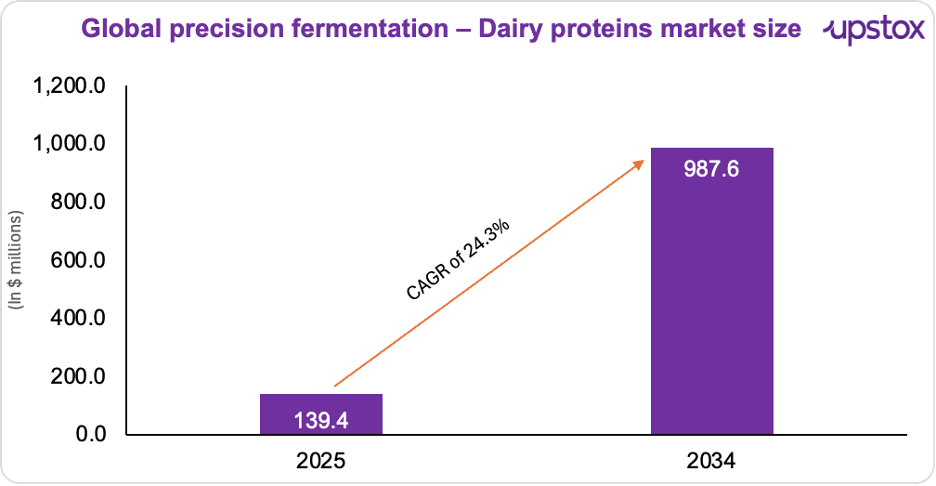

What if milk didn’t need cows at all? What if it was still real dairy; just made differently? That’s the promise of lab-grown milk! With emissions up to 90% lower, costs falling fast, and growth clocking 24% a year toward $1 billion by 2034, the upside is hard to ignore. And that’s why this isn’t just an alt-milk story; it’s a rethink of how milk itself gets made.

Lab grown milk is expected to grow at 24% CAGR and approach $1 billion by 2034

For generations, milk followed a familiar path. Cows were raised, land was grazed, and dairies scaled by adding more animals, more water, and more feed.

Over time, alternatives appeared. Almond, soy, and oat milk removed livestock from the equation altogether. But they also left something behind: dairy’s proteins, taste, and nutritional profile.

Now a different question is being asked.

What if milk didn’t come from a cow; but was still real dairy milk?

That question sits at the heart of lab-grown milk. Unlike plant-based substitutes, this is dairy made without animals. Using precision fermentation, engineered microbes produce the same milk proteins found in cow’s milk, inside fermentation tanks.

For now, lab-grown milk remains a small experiment in a very large industry. In 2024, the global precision-fermented dairy proteins market was valued at just $100 million. Yet the projections are hard to ignore. As costs fall and commercial capacity slowly builds, the segment is expected to grow at a 24% CAGR and approach $1 billion by 2034.

Source: Research gate

Lab-grown milk, explained simply

It’s not milk made in a lab beaker. It’s milk made without cows.

Lab-grown milk usually means producing dairy’s key proteins; whey and casein; using precision fermentation (yes, the method we mentioned above). Scientists insert dairy DNA into microbes like yeast, feed them sugar, and let them churn out milk proteins in fermentation tanks. Mix those proteins with water, fats, and nutrients, and you get milk that behaves like the real thing.

That’s why this is very different from almond or oat milk. Those are plant drinks. Precision-fermented dairy proteins act just like traditional whey and casein, so they work in cheese, ice cream, and protein powders. Now, how is it different from other types of milk?

| Milk Type | Protein (g/100ml) | Shelf Life (Unopened, Refrigerated) | Other Nutritional Info |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cow Dairy | 3.2–3.5 | 12–14 days | Complete protein; naturally rich in B12, iodine, lactose (~4.8 g), riboflavin; higher cholesterol |

| Soy | 2.8–3.5 | 7–10 days | Closest plant-based nutritional match to dairy; often fortified with B12, D |

| Almond | 0.4–1.0 | 7–10 days | Very low protein; calorie-light; not a nutritional dairy substitute |

| Oat | 1.0–3.0 | 7–10 days | Higher carbs; good texture and frothing; nutrition varies by brand |

| Lab-Grown | 3.2–3.5 | Similar to dairy | Bioidentical dairy proteins; lactose-free, cholesterol-free; matches dairy functionality |

Source: Businesswire, eatingwell

Why is it starting to look commercially viable?

For most of history, making dairy was simple. You raised cows, fed them well, and hoped productivity kept up. Precision fermentation changes that equation—and only recently has the math begun to work.

The cost curve finally bent

Back around 2000, producing a single molecule through precision fermentation could cost close to $1 million per kg. Today, that figure has fallen to around $100 per kg for certain molecules. Some industry analyses even suggest sub-$10 per kg could be achievable at scale within the next decade; at least for select proteins.

This drop wasn’t smooth or automatic. It came from years of strain engineering (better-behaved microbes), higher yields, larger bioreactors, and cheaper inputs like sugar and energy. Costs didn’t fall in a straight line. They fell in steps. And we’re currently in one of those step-down phases.

The climate math helps

Multiple life-cycle analyses; both company-sponsored and independent, suggest that precision-fermented dairy proteins can deliver dramatic greenhouse-gas reductions, in some cases up to ~90% lower emissions compared to conventional milk proteins. Land and water use also drop sharply.

The caveat? Outcomes depend heavily on where the energy comes from. Fermentation powered by low-carbon electricity looks far better than coal-heavy grids. This matters for India in particular. According to the International Energy Agency, India is the third-largest methane emitter globally.

Studies suggest livestock contribute around 48% of India’s methane emissions, with cattle doing most of the damage. By 2050, India’s livestock sector alone could account for 15.7% of global enteric methane emissions. Against that backdrop, alternatives to traditional dairy start looking less niche and more necessary.

Functionality isn’t compromised

Unlike plant-based alternatives, precision-fermented proteins are bioidentical to dairy proteins. That means they foam, emulsify, and behave the way food companies expect them to. For coffee, cheese, nutrition powders, and specialised foods, that’s a big deal, and often where plant proteins fall short.

Dairy… without the cow

Supporters of fermentation-based dairy often pitch it as the best of both worlds: real dairy nutrition and functionality, without the environmental and ethical baggage of livestock.

That said, it’s still early days. Companies are experimenting with consumer messaging, regulatory pathways, and where exactly these proteins fit in food portfolios.

Some examples:

-

France’s Verley (formerly Bon Vivant) is developing “functionalised” animal-free whey proteins, with commercial launches planned for 2026.

-

Dutch startup Vivici says its beta-lactoglobulin is drawing interest from premium protein drinks, sports nutrition, and active nutrition brands.

-

ImaginDairy is working with Israel’s Strauss Group to sell cow-free drinks and cream cheese under established brands like Yotvata and Symphony.

Where lab-grown milk is moving from labs to shelves

If lab-grown milk is going to work anywhere first, it has to be in markets that already understand food tech. That’s where progress is showing.

-

In the United States, Boston-based Brown Foods is developing UnReal Milk using mammalian cell culture to replicate the taste, texture, and nutrition of conventional dairy. The product can be turned into butter, cheese, and ice cream, while claiming up to 82% lower carbon emissions, 90% less water use, and 95% less land use. Crucially, the US FDA has cleared several lab-grown and precision-fermented dairy proteins for commercial use. As a result, the US emerged as the core North American market, accounting for $33.7 million in precision-fermented dairy protein sales in 2024.

-

Israel, meanwhile, is fast becoming a global hub for cow-free dairy. Startups like Remilk, Wilk, and Imagindairy are leading the charge. In 2023, Israel’s Ministry of Health approved Remilk’s cow-free dairy proteins, clearing the path for commercial sales. The Israeli food-tech company Remilk has already launched its precision-fermented milk, The New Milk, in cafés and restaurants, and plans a supermarket rollout from January 2026. From early next year, Remilk will sell the product, branded New Milk; through a partnership with Gad Dairies. Two versions will launch first: a 3% fat milk and a vanilla-flavoured option. Both are lactose-free, cholesterol-free, and made without antibiotics or hormones. A separate barista line for cafés will follow shortly after. Pricing, the company says, will be comparable to soy or almond milk; except this one is “real” dairy, just without cows.

Then, there’re others too..

| Country | Current Stage (2025) | Key Companies / Players | Regulatory Status | Notable Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore | Early commercialisation | TurtleTree, Change Foods | World’s fastest food-tech regulator; supportive sandbox model | First Asian hub for novel food approvals |

| European Union | R&D and regulatory review phase | Formo (Germany), Those Vegan Cowboys (Netherlands) | EFSA approval pending; slow but cautious | Strong science base, slower consumer rollout |

| United Kingdom | Pilot stage | Better Dairy, Imagindairy (UK ops) | Novel Foods approval in progress | Regulatory separation from EU may speed approvals |

Source: Businesswire, eatingwell

The India opportunity

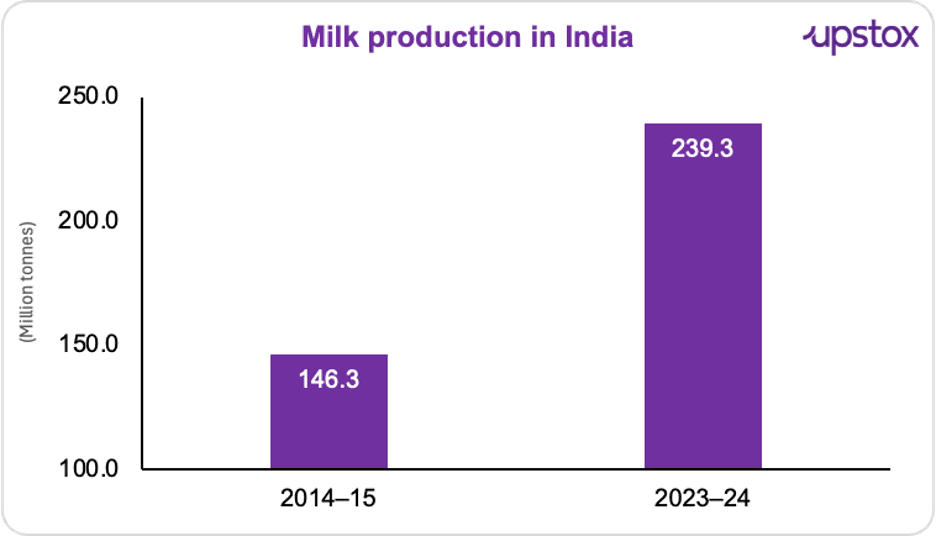

India isn’t just another dairy market. It’s the world’s largest milk producer, accounting for over 24% of global output, and dairy is the country’s largest agricultural product, contributing ~5% to the economy and supporting 8+ crore farmers. Over 100 million rural households depend on livestock, most of them small or marginal farmers, with women playing a central role in production and collection. Milk isn’t just nutrition here, it’s culture, livelihood, and identity. More than 70% of Indians consume it daily.

And yet, nutrition gaps persist. Government data from the Poshan Tracker shows that about 34% of children under five are stunted, 14–15% are underweight, and around 5% are wasted. This is where milk’s role becomes unavoidable. As one of the most accessible sources of high-quality protein, calcium, and essential micronutrients, milk remains central to addressing childhood malnutrition; especially in Anganwadi and school-nutrition programmes.

That context explains why India’s entry into lab-grown milk is cautious, but notable. The sector is still nascent, but momentum is building. For a country that needs more nutrition without disrupting millions of livelihoods, alternative dairy isn’t about replacement yet; it’s about supplementing supply, improving resilience, and widening access in the long run.

-

A small group of startups is beginning to test the waters. Bengaluru-based Phyx44, founded in 2021, uses precision fermentation to produce the full dairy stack; whey, casein, and fats; by programming microbes to make proteins identical to those in traditional milk. The result is animal-free, lactose-free dairy components that behave like the real thing. The company raised $1.2 million in seed funding, signalling early investor interest.

-

Surat-based Zero Cow Factory, also founded in 2021, is working on India’s first animal-free casein and A2 milk proteins, targeting applications across milk, cheese, and other dairy products.

Source: PIB

Outlook

The future of lab-grown milk won’t hinge on one breakthrough, but on economics. And that's where the next phase gets interesting.

Industry models from groups like Roland Berger and GFI/Pathfinding suggest that improving a few core levers; yield (more output per batch), titre (higher concentration), and downstream efficiency (easier purification); can unlock 15–50% cost reductions for the molecules analysed.

In some phases, this translates into 20–30% annual declines, especially as companies move from demonstration setups to multi-10,000-litre bioreactors and rely on co-packing rather than building everything in-house. In short, large and sustained cost drops look plausible during scale-up.

The reality check is more about when, not whether. Precision-fermented milk proteins are still pricier than commodity dairy today, with food-grade costs in the low hundreds of dollars per kg. But the direction of travel matters. As scale improves and processes mature, high-value ingredients and specialised dairy products are likely to find commercial traction first.

Broader, everyday applications may take longer and will hinge on energy costs, scale, and regulation; but for the first time, the economics are starting to line up in a way that makes the transition plausible rather than theoretical.

About The Author

Next Story