Upstox Originals

The $100 billion engine market is heating up — And India wants in

6 min read | Updated on October 24, 2025, 18:05 IST

SUMMARY

India’s finally taking aim at the toughest corner of aviation, building the engines that power its skies. With Indian airlines ordering over 1,300 aircraft in the past two years and the global engine market projected to reach $125 billion by 2030, the timing couldn’t be sharper. The piece traces how the country is moving from fixing aircraft to mastering propulsion, as partnerships with GE, Safran, and Rolls-Royce start opening doors long bolted by IP and expertise.

Even a 2–3 % foothold in this global engine market could translate into ~$2.5-3.5 billion worth of cumulative business by 2030 for India

Now, India’s attention is shifting to the hardest part of flight, mastering the engine itself.

From hangars to hearts

India is still learning to fix what it flies, but it’s already eyeing the next big leap: building what makes it fly.

That’s like trying to design a car engine while still learning to service it, bold, yes, but also how India’s aviation story has always moved: skipping a few gears when the world wasn’t watching.

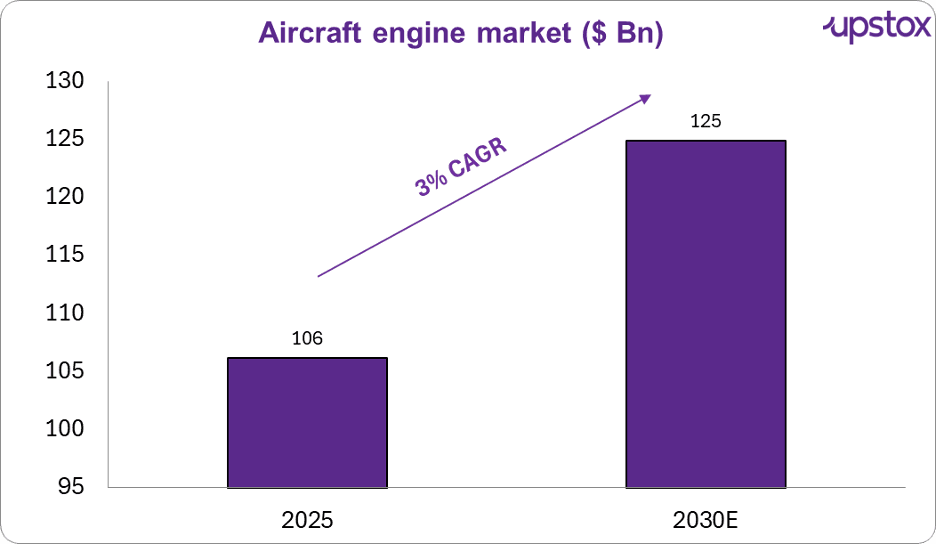

Sources: Mordor Intelligence

And the timing couldn’t be better, the global engine market is quietly revving up and expected to grow at a CAGR of around 3% till 2030, steady, not spectacular, but extraordinary for a market already worth $106 billion. This isn’t growth driven by shiny new jets; it’s powered by older ones staying in the air longer.

While the 3% growth is not exciting to behold, the truth is that there are pockets and areas of opportunities beyond simply selling industries.

Engines don’t just get sold once. They earn for decades through overhauls, spares, and service contracts, aviation’s quiet subscription model. Every delayed aircraft delivery or extended flight hour keeps the revenue meter running, a quiet gain few outside the industry notice.

That’s where India’s opportunity lies. Even a 2–3 % foothold in this global market could translate into ~$2.5-3.5 billion worth of cumulative business by 2030, from assembly lines and component manufacturing to engine overhauls and testing. That’s not a side bet; it’s a strategic opening in one of aviation’s most protected segments.

With repair slots full and supply chains stretched, engine makers are now hunting for new capacity and partners. For India, that gap looks familiar; it’s the same opening that turned maintenance into its next big aviation business. The hangar built the muscle, engines will test how strong it’s become.

The world’s most exclusive market

If the aircraft itself is the showpiece, the engine is the secret recipe, and only a handful of chefs in the world know it.

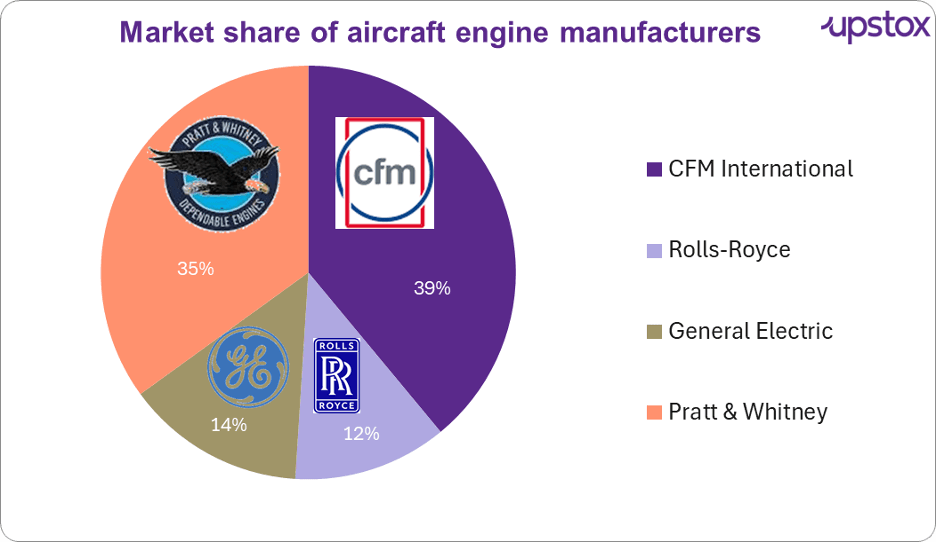

Source: Statista

Four companies, CFM International (GE + Safran), Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, and GE Aerospace, control almost 99% of the global aircraft engine market, powering nearly every commercial jet in the sky.

Their dominance comes from decades of science, certification, and closely guarded IP. A modern turbofan runs hotter than molten rock, spins faster than a Formula 1 engine, and takes years to test before a single flight, a business as profitable as it is protected. Engine makers don’t compete on volume; they compete on trust. Once an airline chooses an engine, it’s locked in for decades through maintenance and upgrades, less a market, more a membership.

But those walls are starting to crack, order books are full, OEM shops stretched thin, and the world is quietly looking for new partners to share the load. For India, that’s an opening worth noticing.

India isn’t the only one trying to crack the code. China has been developing its CJ-1000A engine for the COMAC C919 jet for nearly a decade but still struggles with reliability and certification. Turkey’s TEI and South Korea’s Hanwha Aerospace are racing to build military turbofans, while Japan has merged its fighter engine programme into a joint project with the UK and Italy.

Despite billions in R&D, few have crossed the certification finish line, a reminder of how high the barriers really are.

That’s why India’s model of co-production and phased technology absorption stands out. Instead of reinventing the turbine, it’s learning to build around it, a quieter, steadier way into aviation’s hardest club.

Breaking into that circle takes more than ambition; it takes persistence, partnerships, and timing. India’s now finding all three.

India’s entry point

After years of building airframes without the engines to power them, India is finally edging into the core. In 2023, GE Aerospace and HAL signed a deal to co-produce F414 jet engines for the Tejas Mk2, the first time an American engine of this class will be made in India. The agreement includes about 80% technology transfer, and production is expected to begin by 2027–28, once testing and tooling are complete.

Safran is investing nearly $200 million in a new engine test and manufacturing facility in Hyderabad, designed to handle M88 and LEAP-series engines and to support future indigenous projects.

Rolls-Royce is collaborating with HAL and DRDO on smaller gas turbines for trainers and UAVs, while private players like Godrej Aerospace, Tata Advanced Systems, and L&T supply turbine housings, compressor casings, and test modules. It’s still early days, India isn’t making full engines yet, but it’s finally building the ecosystem that will.

The economics of thrust

A modern jet engine may sell for $10–20 million, but that’s just the sticker price. Over its 30–40 year lifespan, it can generate $40–60 million in after-sales revenue from maintenance, spares, and service contracts, the real money in propulsion’s long game. That’s what makes India’s new partnerships so strategic.

They plug local firms into a revenue stream that never stops. Analysts estimate the F414 programme alone could generate about $1–1.2 billion in local value over its lifecycle, with ripple effects across alloys, castings, and precision machining. Every turbine built or tested here adds not just thrust to India’s skies, but momentum to its manufacturing base.

The IP challenge

Every deal in aviation comes with fine print, and in engines, that fine print is everything.

India’s biggest barrier isn’t ambition, it’s access. Jet engines sit behind layers of patents, export controls, and metallurgy guarded like state secrets. The GE–HAL F414 deal has cracked that door open, giving India a look inside the process, not the blueprint.

Take single-crystal turbine blades: they’re grown, not forged, and mastering them separates engine makers from assemblers. India once tried to reverse-engineer them; now, through collaborations with GE and Safran, it’s finally learning the method, not just the machine.

The Kaveri engine, too, has turned from setback to stepping stone, its failures teaching what textbooks couldn’t. India’s moving from licence to literacy, building the fluency to design around the patents it can’t yet own.

Because in aviation, real autonomy isn’t about having the blueprint, it’s about knowing how to redraw it.

Outlook

India’s aviation climb is shifting from fixing what it flies to powering it. The coming years won’t be about perfect engines, but about building the ecosystem that can make them. The hangar-built India’s confidence; the turbine will test its conviction and, perhaps, define its altitude.

By signing up you agree to Upstox’s Terms & Conditions

About The Author

Next Story