Upstox Originals

How Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation led to an economic spiral

.png)

6 min read | Updated on July 18, 2025, 13:35 IST

SUMMARY

Imagine holding a Z$100 trillion bill in your hands—yet being unable to buy even a loaf of bread. Imagine your salary losing value before you even reach home from work. This was the reality of Zimbabwe's hyperinflation. Prices doubled within hours, and the local currency became nearly worthless. How did this happen? This article examines the economic and policy decisions that led to one of the worst hyperinflation episodes in history.

In early 2009, Zimbabwe released a Z$100 trillion note

Between 2007 and 2009, Zimbabwe experienced one of the worst cases of hyperinflation in world history. At its peak in November 2008, the annual inflation rate was estimated at 89.7 sextillion percent (that’s 89.7 followed by 20 zeros!). Prices were doubling every 24 hours, and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe continued to print money in increasingly higher denominations—eventually releasing a 100 trillion Zimbabwean dollar note in early 2009.

Yet, it could barely buy a few groceries. But how did things get this bad? What decisions triggered such a collapse?

The curse of hyperinflation: When money loses meaning.

Hyperinflation occurs when prices rise by more than 50% per month, quickly eroding the value of a currency. It disrupts economic stability, reduces trust in monetary policy, and can take decades to recover from. If not addressed properly, it can also recur.

The root causes of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation: where it all started

In 1980, most of the fertile farmland in Zimbabwe was owned by white settlers, leaving many Black Zimbabweans landless. Under President Robert Mugabe, the government launched land reforms to correct this imbalance and win popular support. Over the next few decades, farmland was forcibly taken from white owners and handed over to locals.

These commercial farms were the backbone of Zimbabwe’s economy. The new owners, though well-meaning, lacked the resources and training for large-scale farming. Many turned to growing just enough for their families, and food production collapsed, falling by 60% between 2000 and 2010. This triggered food shortages.

As agriculture crumbled, its ripple effects were felt across industries—by 2002, over 700 companies had closed, disrupting exports and creating shortages of basic goods. The financial system too began to strain, as banks that once relied on land as collateral faced mounting bad debts, and foreign investment dropped sharply from $444 million in 1998 to just $3.8 million by 2003.

To cope with its growing obligations, the government turned to printing more money, which only accelerated inflation and led to multiple rounds of currency redenomination. Meanwhile, governance challenges, including inefficient public institutions and limited transparency, made it harder to regain investor trust or plan for long-term recovery.

The peak of economic collapse: when money became worthless By November 2008, Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation reached an unprecedented level. To understand the full scale of the economic collapse, let’s compare key economic indicators before hyperinflation and at its peak.

| Parameter | Before hyperinflation - 1980 | Peak of hyperinflation - 2008 |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Inflation (%) | 5.4 | 489 billion |

| Average month-on-month inflation | 0.5 | 2600.2 |

| Largest currency Denomination | Z$ 20 | Z$ 100 trillion |

| Most widely used currency in transactions | Zimbabwean dollar | US dollar, South African rand and the Botswana pula |

| Exchange Rate (in $) | Z$ 0.6 | Z$4 million |

| Real GDP growth (%) | 14.6 | -17.0 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 10.8 | 94.0 |

Source: Globalisation and Monetary Policy Institute 2011 Annual Report

How hyperinflation affected the daily lives of Zimbabweans

Between 1998 and 2008, Zimbabwe’s per capita income dropped from $1,640 to just $661 a year, as hyperinflation took hold—by mid-2008, it took Z$100 billion to buy just three eggs. Government-imposed price controls in 2007–08 led to shortages and empty shelves, as businesses couldn’t sustain selling below cost.

As formal markets collapsed, a parallel economy took shape, where essentials were traded in US dollars, rents were paid in food, and black-market rates ruled. By 2007, formal employment had disappeared for eight out of ten people, and emigration surged (from 6% of the total population in 2005 to 9.9% in 2010) as many sought stability abroad.

What did the government do to fight with this chaos In a desperate attempt to control inflation, the Zimbabwean government banned price hikes and kept printing money—then kept redenominating its currency by chopping off zeros. But without real reforms or backing, this failed miserably.

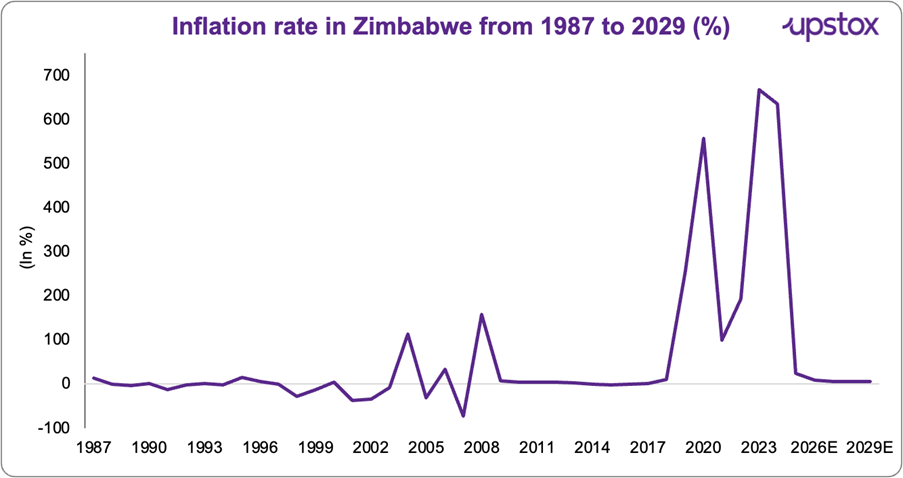

Eventually, in 2009, they abandoned the Zimbabwean dollar and adopted foreign currencies like the US dollar, Euro and the South African Rand which finally brought inflation under control. However, when they reintroduced a local currency in 2019—the RTGS dollar—hyperinflation made a comeback.

Source: Statista

After the 2008 inflation wave, to regain control, the government ditched its currency in 2009 and allowed foreign currencies like the US dollar to take over. This move brought much-needed stability, and inflation dropped significantly over the next few years.

But in 2019, trying to reclaim monetary control, the government introduced the RTGt (Real Time Gross Settlement) dollar—a move that backfired as inflation again soared above 500%. In 2023, a new chapter began with the launch of Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG), a digital currency backed by gold.

Can ZiG do the trick?

ZiG is Zimbabwe’s sixth currency in 16 years, and the government believes this one might finally work because it’s backed by gold. The idea is that the money supply will be limited to how much gold the country holds, which should keep inflation in check. But there’s a catch. People don’t trust the system—not after years of broken promises, underreported money printing, and collapsing currencies.

Most transactions still happen in US dollars, and black-market trading continues to weaken the ZiG. Unless the government wins back public trust and ensures real transparency, ZiG might just go down the same road as its predecessors.

Key lessons to learn

Zimbabwe’s experience shows that economic stability begins with thoughtful spending and a currency that holds its value. When land reforms disrupted agriculture, it highlighted how protecting property rights is key to long-term growth. The crisis also revealed the importance of strong leadership and political stability in gaining investor trust.

Relying too much on one sector, like farming, made the economy vulnerable, diversification could have softened the blow. And in tough times, safety nets like healthcare and education matter. Staying connected with the global economy and always having a backup plan can help countries bounce back from even the hardest of falls.

By signing up you agree to Upstox’s Terms & Conditions

About The Author

Next Story