Upstox Originals

Are India’s widening current account deficit fears overstated?

6 min read | Updated on November 19, 2025, 15:49 IST

SUMMARY

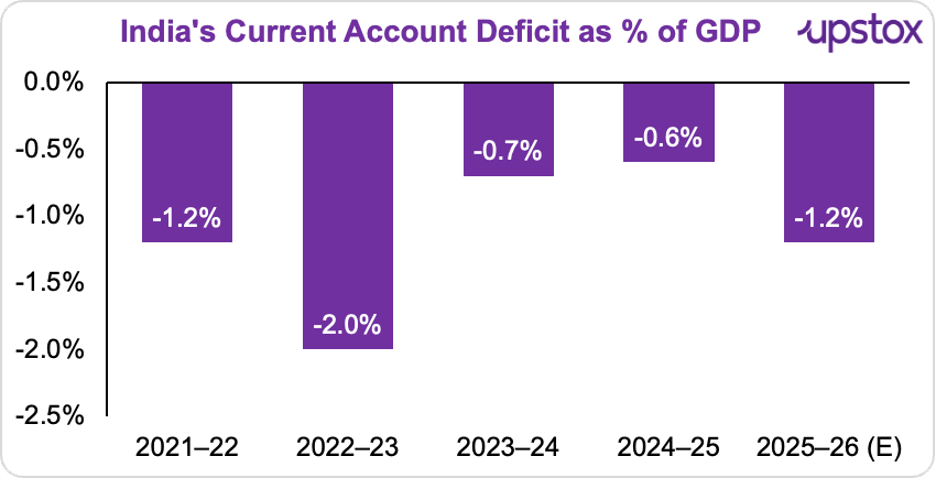

Starting FY26 at just 0.2% of GDP, India’s current account deficit is projected to widen to 1.1 - 1.5% later this year, citing rising imports, higher precious-metal prices, and global trade uncertainties. But what do the underlying numbers reveal? This article examines whether fears of a sharply widening CAD could be, and whether a 1.5% CAD is really something to worry about.

From 0.2%, India’s current account deficit is expected to widen to 1.1-1.5%.

India got off to a strong start in FY26. How strong? The nation’s current account deficit (CAD) shrank to just 0.2% of GDP ($2.4 billion) in Q1, supported by softening oil prices earlier in the year, subdued goods imports, and a stable services surplus.

Despite the stellar Q1 data, the general consensus among economists is to be cautious. They suggest that if the current global pressures continue, India's CAD might increase, approaching 1.2% of GDP by the end of FY26, driven by rising non-oil imports, higher gold and silver prices, and global trade disruptions.

Source: RBI

But, what do the numbers suggest?

First, what actually is the current account deficit?

The gap between a nation's payments and receipts from international trade in products, services, investment income, and transfers is known as the current account deficit (CAD). The CAD is an important external sector indicator for a developing economy like India.

-

Healthy investment, trade openness and growth-oriented imports (technology, machinery) can all be reflected in a modest or moderate CAD.

-

On the other hand, a high or rising CAD may be a sign of vulnerability due to excessive borrowing, pressure from currency depreciation, reserve depletion, or reliance on erratic capital flows.

-

The CAD's size, composition and trends are crucial factors for investors and policymakers to consider when evaluating external resilience. Is the CAD outlook actually as worrisome as analysts claim?

Let’s examine

Oil imports

According to the Nomura report, there’s a stress metric; every $10 increase in crude potentially adds 0.4% of GDP to the CAD. Yes, India’s dependence on crude remains high, but there’s a positive thing; oil prices have been remarkably stable.

Brent is projected to average $68.76/bbl this year, lower than last year’s $80.56. Despite geopolitical tensions, monthly import bills have not shown the kind of volatility that typically threatens external balances.

So far in FY26, oil has not been the pressure point that analysts feared. That said, oil prices tend to be volaitlie and as such could be a wild card.

Merchandise imports

Another worry is that as domestic demand grows, India's imports of capital goods, electronics, and machinery would increase. However, the evidence suggests a much more measured reality.

The merchandise trade deficit increased slightly from $63.8 billion to $68.5 billion in Q1. More importantly, the August 2025 deficit of $26.49 billion was significantly less than the August 2024 deficit of $35.62 billion.

Yes, the deficit did reach a 13-month high in September ($32.15 billion), but it wasn't caused by structural overheating but rather by seasonal import demand for goods like electronics, gold, and silver ahead of the holiday season. With the season now behind us, CAD’s stabilisation in the upcoming months is critical.

Restrictive trade policies

Geopolitics, particularly the US tariff shock, is the subject of a third concern. In August 2025, merchandise exports actually increased 6.7% year over year to $35.1 billion thanks to stable core exports, gasoline, and jewelry. At the same time, imports cooled considerably. According to Crisil, merchandise imports decreased 10.1% year over year, from $68.53 billion to $61.59 billion.

India recently signed a natural gas purchase agreement with the USA. This could potentially be the first step towards de-escalating the situation with the USA and bringing down the tariff burden

Rising precious-metals prices

The sharp rise in precious-metal prices is often cited as a CAD risk because India is one of the world’s largest importers of gold and silver. And yes, prices are rising again in 2025 - 26. But this isn’t a new shock; India has already weathered a strong metals rally over the past year.

The World Gold Council reports that demand from central banks, safe-haven purchases, and geopolitical unpredictability all contributed to a 23% increase in gold prices in 2024. As industrial demand increased, silver also saw significant gains, increasing by 20–22% over the course of the year.

To put it simply, India managed to produce a CAD of only 0.2% in Q1 FY26 despite having already managed a year in which both major precious metals increased by around 20–23%.

What actually gives India comfort?

If these traditional risks aren’t as threatening as they appear, then something else must be keeping India’s CAD anchored.

Remittances

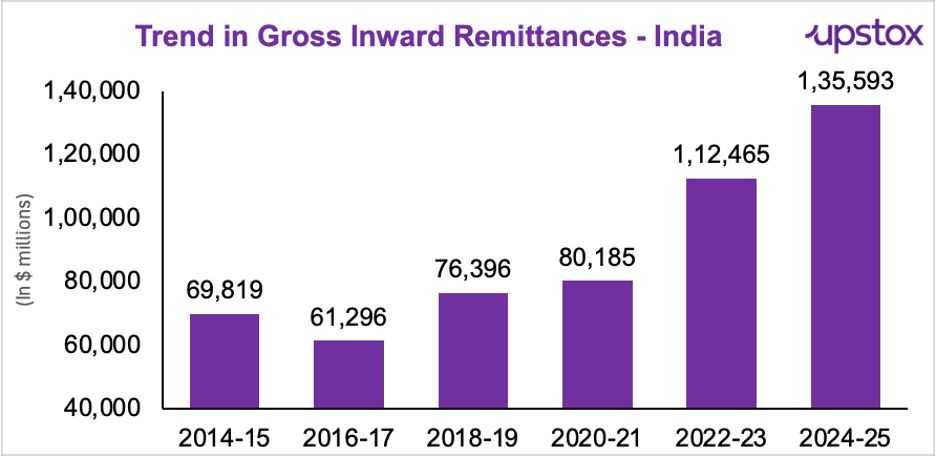

India has been the world’s largest recipient of remittances for over two decades. These transfers, largely from the Gulf, North America, Europe and Southeast Asia; are extraordinarily stable because they are driven by migrant household income rather than financial cycles.

What makes remittances such a powerful shock absorber? They depend on migrant household income, not volatile financial markets. Whether global interest rates rise or fall, remittances remain steady because they flow from millions of workers and professionals; not from investors.

The latest numbers are record-breaking:

-

$135.46 billion in remittances flowed into India in FY25; the highest ever

-

According to RBI’s BoP data, gross inward remittances (“private transfers”) grew 14% YoY

-

Remittances have more than doubled from $61 billion in FY17 to over $135 billion in FY25

These inflows consistently narrow the current account deficit because they enter the balance of payments as a credit item. Most importantly, they rarely experience sharp reversals; unlike FPI flows or commodity-linked export revenue.

Source: TOI

Services Exports

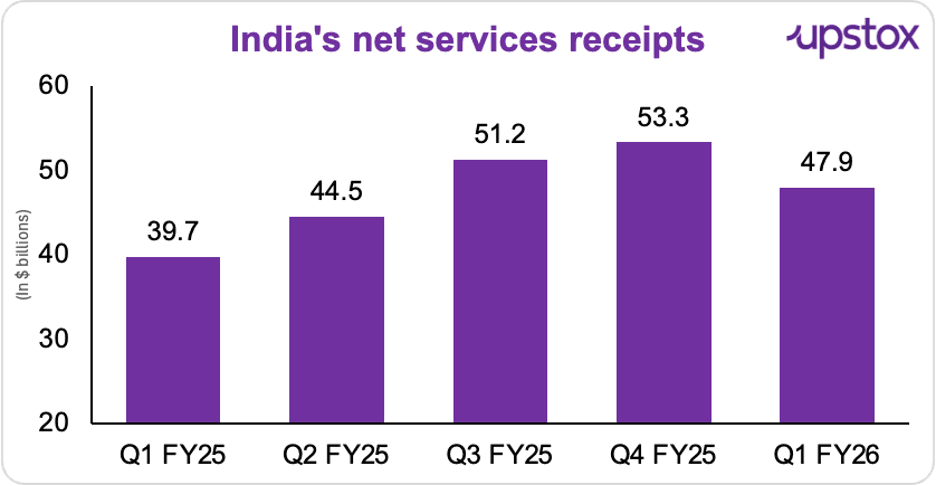

Beyond remittances, India’s services exports have become a high-margin, globally competitive growth engine. These now span software and cloud services, global capability centres, business and consulting services, digital platforms and R&D.

In Q1 FY26, India’s net services receipts rose to $47.9 billion, up from $39.7 billion a year earlier, helping absorb much of the widening merchandise trade gap.

Source: The Hindu

The road ahead

Most economists agree that India’s CAD will inch up in the coming quarters, but the numbers still sit comfortably within a safe band.

Aditi Nayar, Chief Economist at ICRA, puts it simply: baseline CAD for FY26 is around 1.1% of GDP; even the worst-case 1.5% is manageable.

But should we be concerned? Why? Because even as the goods deficit widens, India's two strongest buffers continue to do the heavy lifting.

Remittances are at record highs and remain steady even when global markets turn volatile.

Quarter after quarter, services exports, which include IT, consultancy, cloud, GCCs, and R&D, continue to generate sizable, superior inflows. When combined, these offer an offset to the strain brought on by an increase in imports.

So, should we be concerned about a 1% - 1.5% CAD?

We should be vigilant. India’s ability to maintain a manageable CAD will depend on how effectively these buffers are utilised and how they interact with evolving global pressures, including oil prices, trade restrictions, and geopolitical developments.

By signing up you agree to Upstox’s Terms & Conditions

About The Author

Next Story