Business News

UK panel flags ‘serious delivery risk’, implementation challenges on FTA with India; here’s what it said

.png)

4 min read | Updated on January 22, 2026, 11:51 IST

SUMMARY

In a report on the UK–India Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), the House of Commons Business and Trade Committee said projected tariff savings of around £400 million a year, rising to £3.2 billion annually over a decade, could be undermined by cuts to export support staff.

The pact is aimed at doubling bilateral trade in goods and services to $112 billion from $56 billion at present.

Britain’s most economically significant post-Brexit trade deal could fall short of its promised benefits unless the government urgently strengthens export support and tackles persistent non-tariff barriers in India, a parliamentary committee warned on Wednesday.

In a detailed report on the UK–India Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), the House of Commons Business and Trade Committee said billions of pounds in tariff savings projected under the deal risk being undermined by cuts to export support staff and by complex regulatory hurdles faced by British firms operating in India.

The findings were published as the government began tabling the agreement in parliament for ratification.

The committee said duty savings for UK exporters could amount to around 400 million pounds a year once the deal enters into force, rising to as much as 3.2 billion pounds annually after 10 years as export volumes grow.

Government estimates suggest the agreement could raise UK gross domestic product by 4.8 billion pounds by 2040 and increase bilateral trade by 25.5 billion pounds compared with a no-deal scenario.

“This is the biggest free trade deal since Brexit with the potential to deliver billions in tariff savings for UK exporters, boosting growth and creating new jobs,” committee chair Liam Byrne said.

“But Parliament is being asked to ratify a deal promising billions in tariff savings while the government is simultaneously cutting nearly 40% of the export staff needed to help exporters make the most of this new bargain. That is a serious delivery risk,” he added.

The report said ratification should be seen as “only the start” of the process, urging the government of Prime Minister Keir Starmer to set out a clear, well-resourced implementation plan ahead of the agreement’s entry into force.

The committee recommended assigning explicit ministerial responsibility for overseeing implementation, supported by adequate budgets, and publishing regular data on how widely tariff preferences are being used by businesses.

“Ministers must now table a clear plan backed with real resources to make access on paper into exports in practice,” Byrne said.

The panel highlighted India’s extensive non-tariff barriers as a major obstacle to realising the deal’s full potential, warning that regulatory opacity, inconsistent enforcement, state-level frictions, export health certification requirements and the growing use of Quality Control Orders posed “a material risk” to UK exporters.

India’s “sprawling administrative system and complex and evolving red tape” mean that the government must play an active role in monitoring barriers and intervening rapidly when problems arise, the report said.

While tariff liberalisation under the agreement is expected to be significant in sectors facing historically high Indian tariffs, the committee cautioned that long staging periods, complex rules of origin and administrative burdens could limit uptake, particularly among small and medium-sized firms.

Stakeholders in the UK dairy industry raised concerns about limited reciprocal access to the Indian market, while increased import competition is anticipated in sensitive sectors such as textiles and ceramics, the report said.

The committee called on the government to ensure that trade remedies and bilateral safeguard mechanisms are accessible, timely and proportionate, with clear guidance for businesses and active monitoring of vulnerable industries.

The agreement was judged to provide greater certainty and stability for UK services providers but limited new market access. Its practical value would therefore depend heavily on effective implementation, including progress on mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

“The Government should identify priority sectors for mutual recognition within the timeframe set out in the Agreement and set out clearly how it intends to progress arrangements of greatest commercial value,” the report said.

The committee also noted that the absence of a concluded investment chapter or bilateral investment treaty meant enhanced investor protection “remains an ambition rather than a secured outcome”, urging ministers to re-energise talks on a future treaty.

The panel also flagged the lack of binding human rights provisions in the agreement, calling on the government to set “clear and enforceable expectations” for UK businesses establishing supply chains with Indian partners.

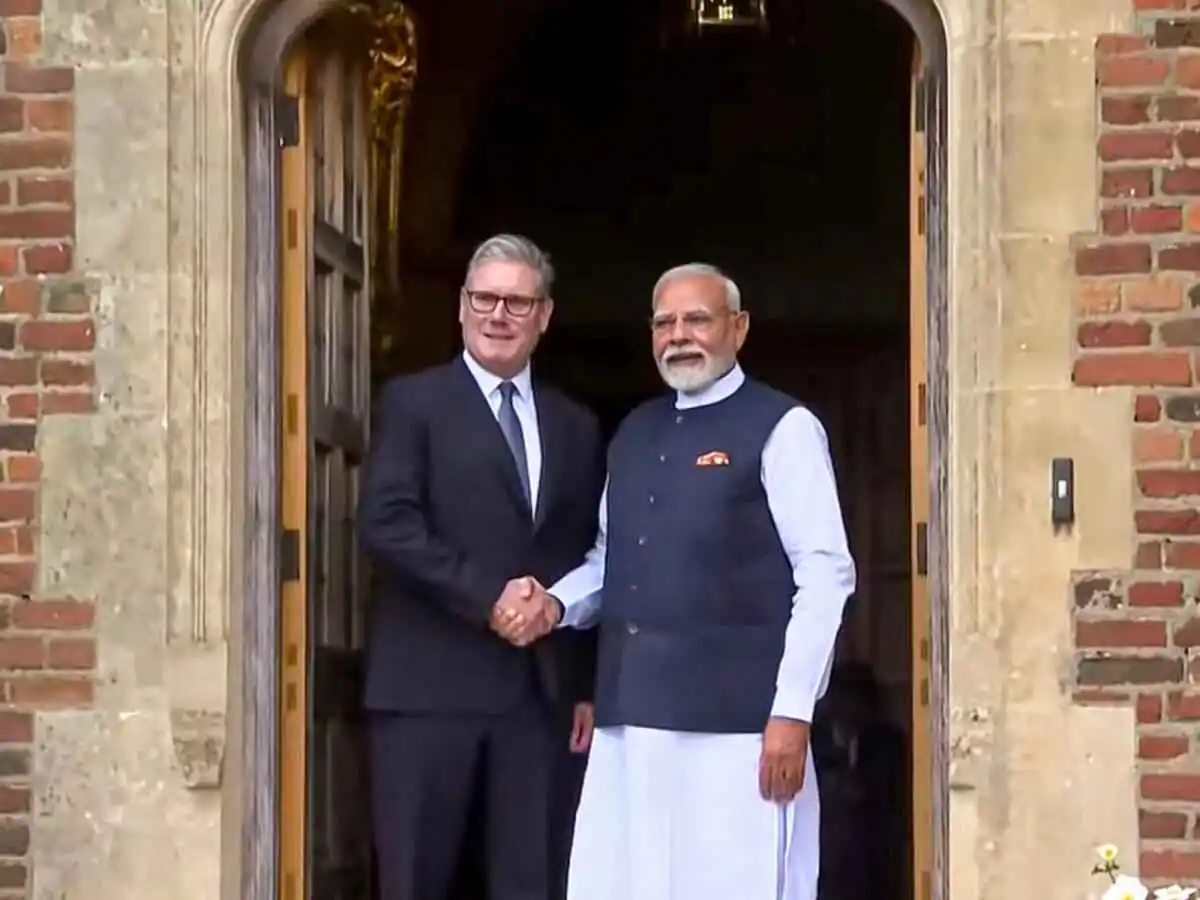

The CETA was signed during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Britain in July last year and has been described by both governments as a landmark pact. UK–India trade stood at 47.2 billion pounds in 2025, according to official data.

The agreement is expected to slash average tariffs on British exports to India to about 3% from 15%, benefiting products ranging from cars and aerospace parts to spirits, cosmetics and soft drinks. Almost 99% of Indian exports, including textiles, footwear, gems and jewellery, seafood and engineering goods, are set to gain duty-free access to the UK market.

About The Author

Next Story